Narrative Arcs

Excerpt

I’m Mary Finch, I’ve lived on the estate for forty-three years.

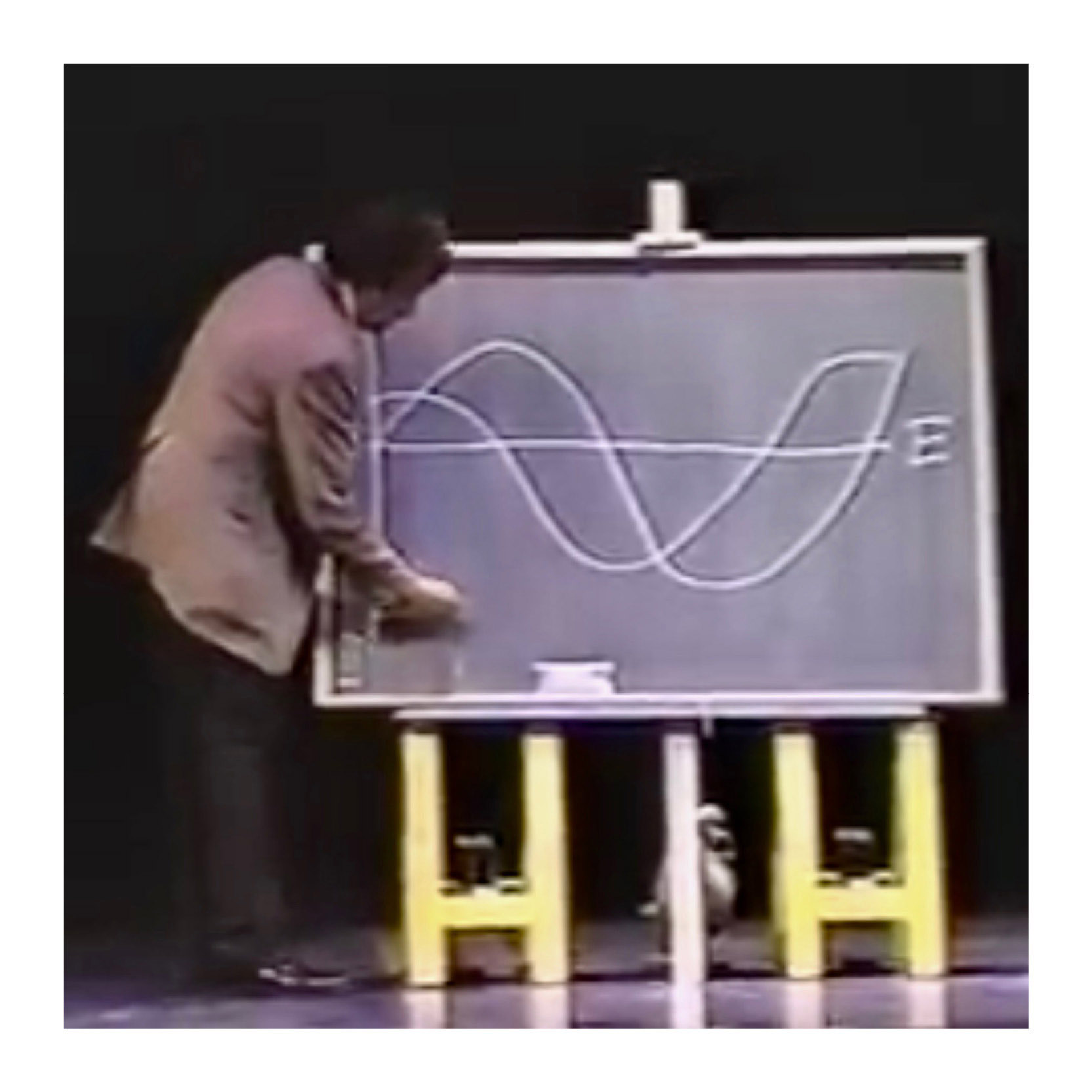

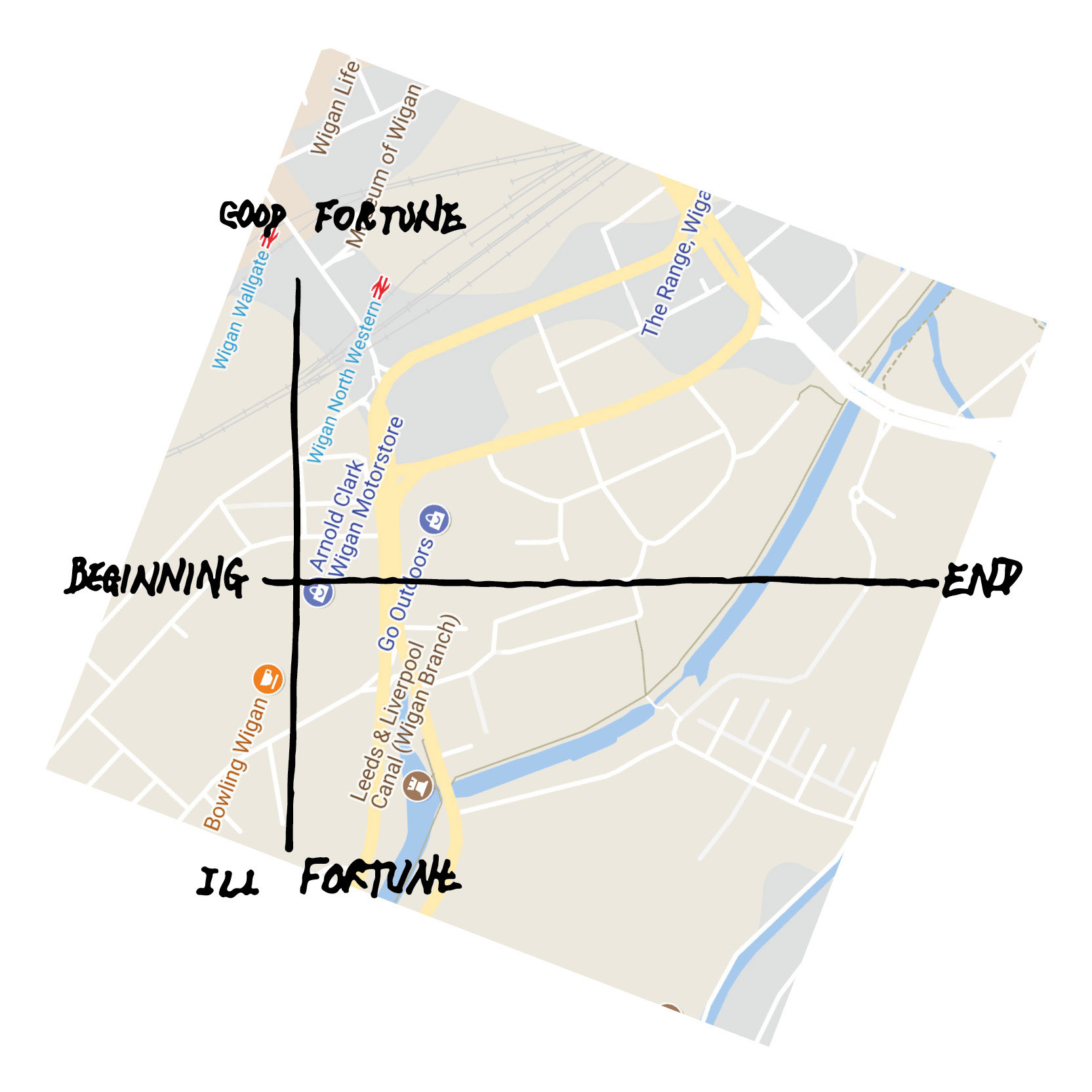

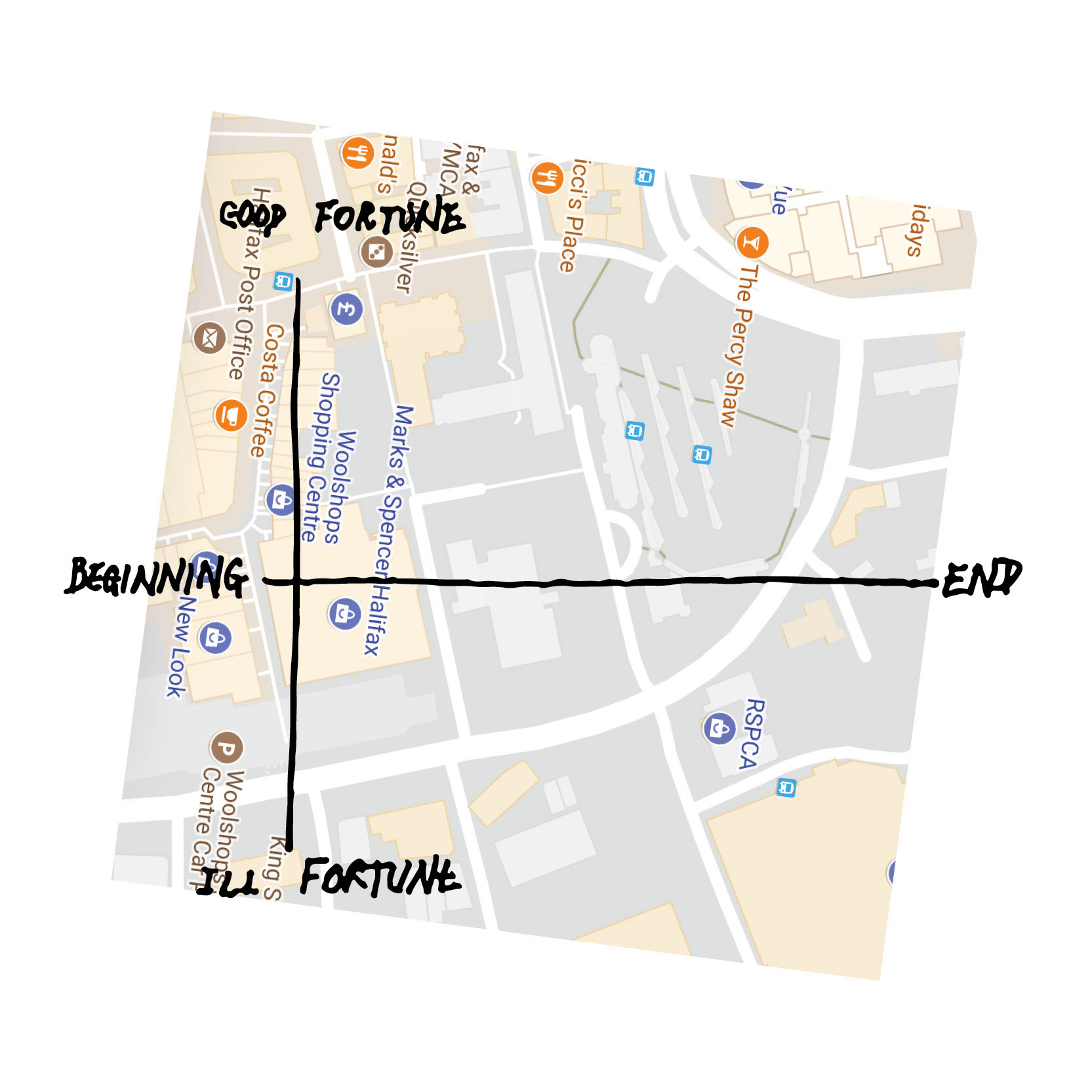

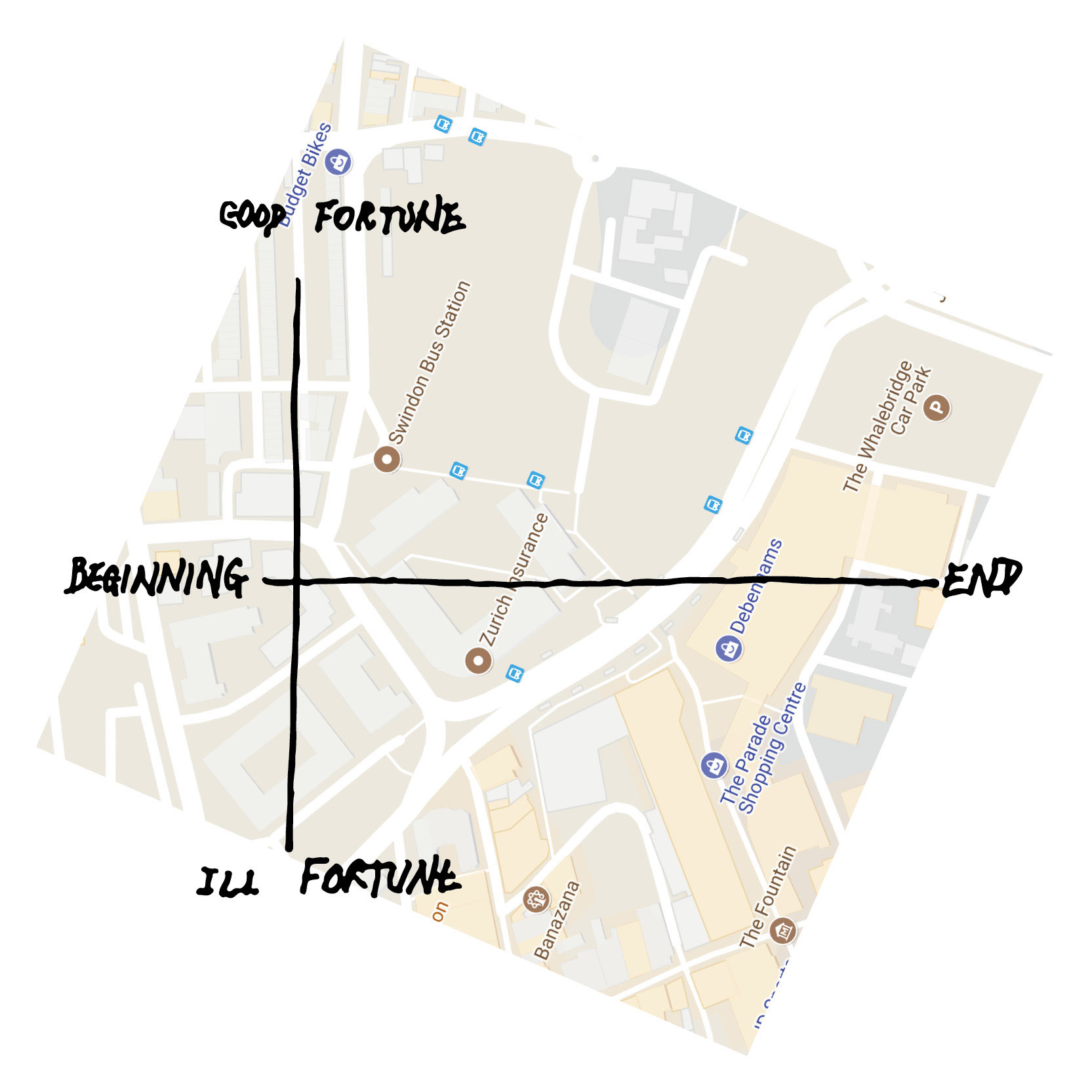

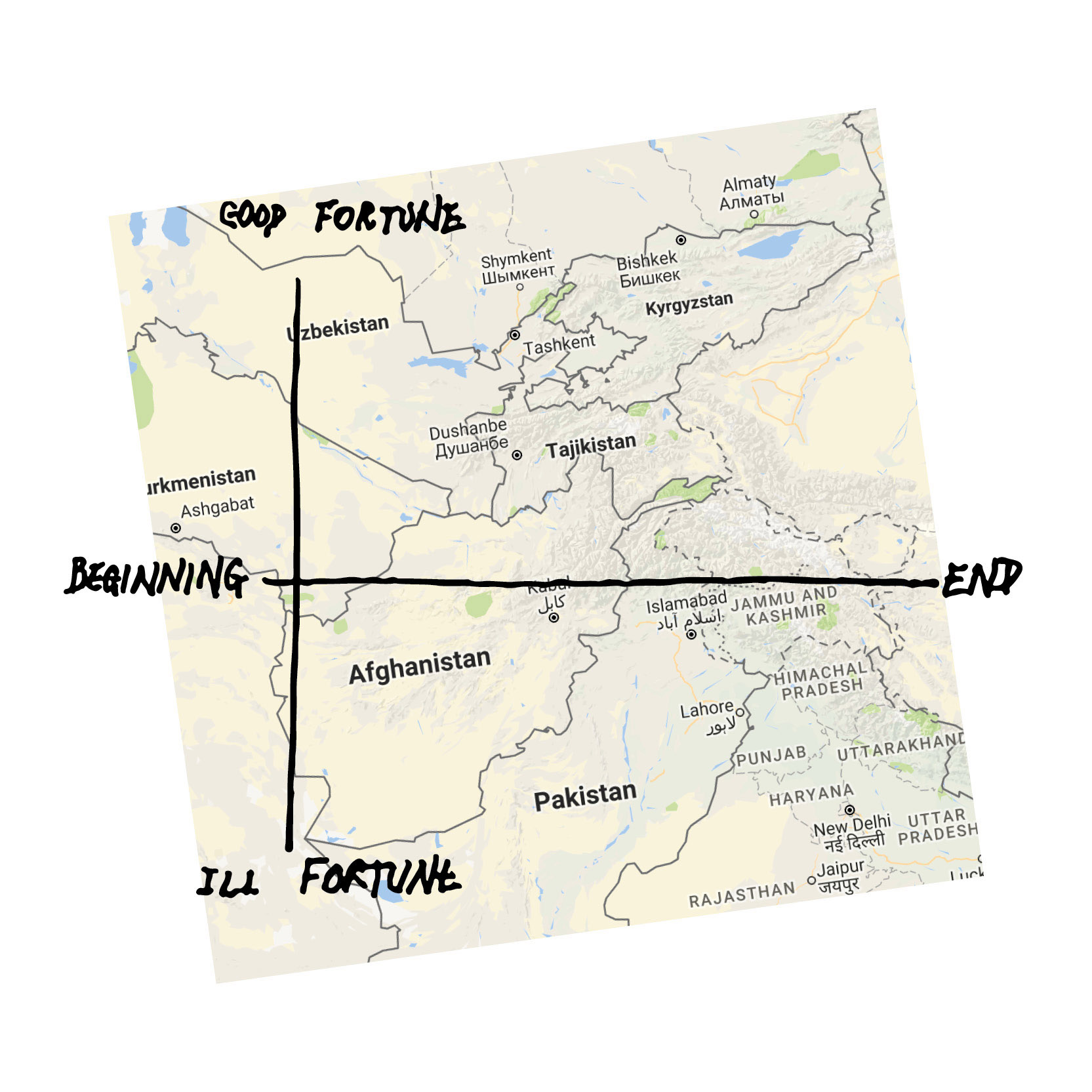

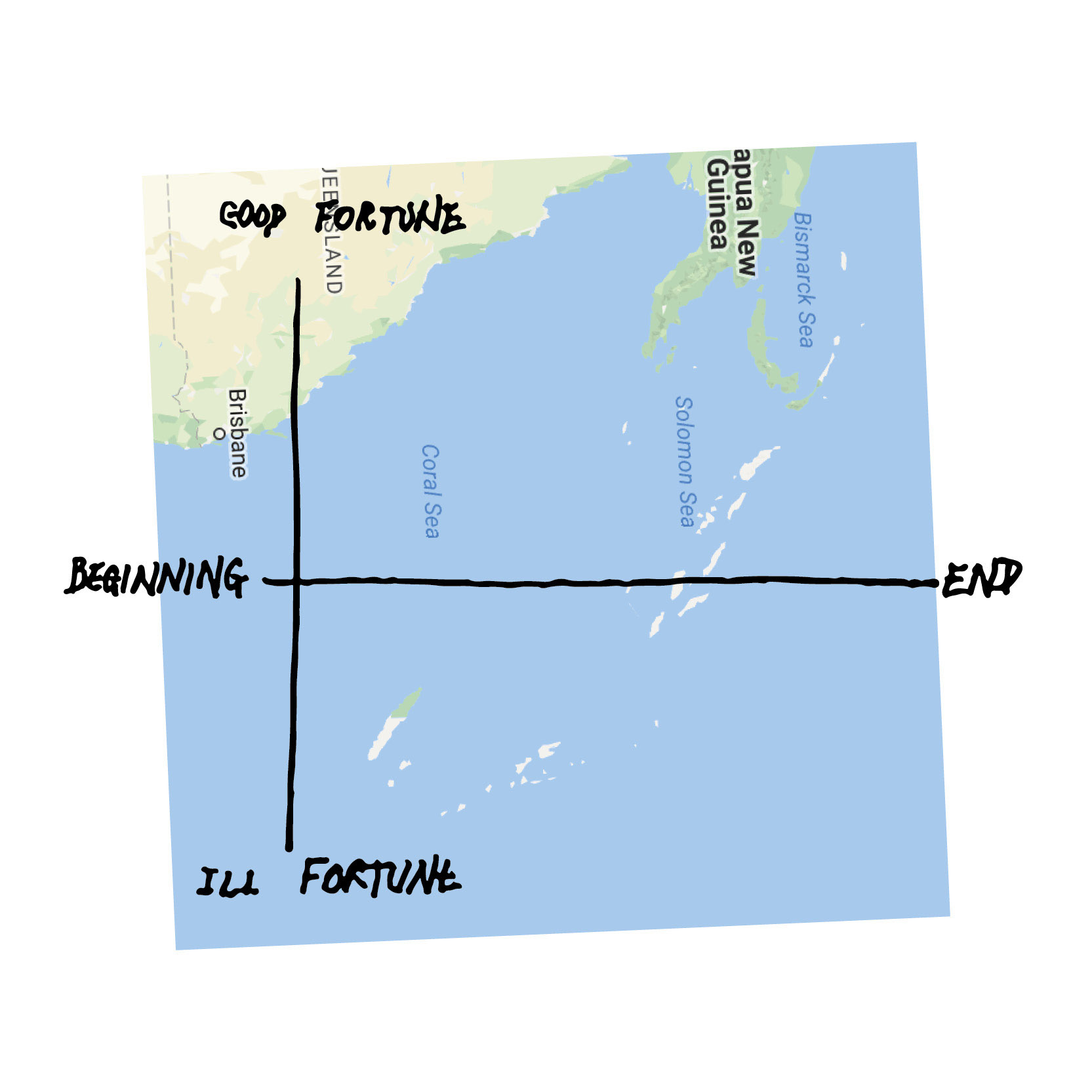

A man scratches chalk against board. “I want to share with you something I’ve learned.” The students in tiered seating break into laughter. It’s not the first time he has done this. “I’ll draw it on the blackboard behind me so you can follow more easily. This [drawing a vertical line] is the G-I axis: good fortune to ill fortune. Death and terrible poverty, sickness down here [pointing to bottom of line], great prosperity, wonderful health up there [pointing to top]. This [drawing a horizontal line] is the B-E axis. B for beginning, E for entropy. Now this is an exercise in relativity, the shape of the curve is what matters, not its origin…”

Had two children: Susan and Brian.

In his lectures on the universality of fiction, Kurt Vonnegut stands beside a blackboard onto which he plots the common patterns of stories in arcs of chalk. The complexity of Hamlet, Cinderella or the New Testament absurdly distilled. An opportunity, Vonnegut explains, to share the thwarted thoughts of his rejected Master’s thesis. He draws a single line charting the central character’s progress, sinuously or abruptly stepping from good to ill fortune and back again. The students laugh because they know it is too easy.

I loved working in the school, started off as a dinner lady.

That a story has a shape feels true. It begins at the beginning and ends at the end. Things follow on from one another, actions have consequences and time marches onwards. The contained nature of a story is an ancient ideal, an idea of what a story is, first set out by Aristotle. “It should have”, he said, “for its subject a single action, whole and complete, with a beginning, a middle, and an end”, the point where the chalk hits and leaves the blackboard, and its unbroken line between. Much of Aristotle’s Poetics were lost, much has been disregarded as outdated, but the idea of the shape of a story remains. Narrative arcs shape how we tell stories to each other, about each other, about ourselves or about a place.

It was brilliant.

Those who study the form and function of stories, such as Jerome Bruner, Ruth Finnegan, Barbara Hardy, Karl Weick, see humans as storytelling animals. It is the way we share the mess of life with one another, bundled up in a form that leaves out all time spent waiting for the kettle to boil. These stories structure our lives in the retelling, constructing patterns of beginnings and endings out of a “flowing soup”. Eventually the story of our day becomes the day itself, not how it was, but how it was told. An accumulation of all the stories you tell shapes how others see you and, eventually, the stories shape how you understand yourself.

I became very ill in March.

Our stories as individuals nest inside and overlap with the stories of those around us, relegating one another to supporting characters or elevating us to heroic roles. So, why does a story about a place matter?

Delores, if I’m not around for a day or two, Delores will knock to see if I’m fine.

Imagine this: A borough plagued by ill fortune. A quest for transformation is rewarded. Its people revel in good fortune and off-scale happiness. “We have a story to tell”, its Borough Council proclaims, “Newham is being transformed from being an underperforming local authority, only three or four years ago, to being at the leading edge of local government thinking and development”.

When I walked in here, God, I must admit I was over the moon.

Visitors to Newham Council’s website used to be greeted by the message “Newham — the most deprived authority in England”, an inauspicious start to any story. Vonnegut warns, don’t begin a story with tragic ill fortune, “not too low, nobody wants to be depressed”. So the council decided to update the moment of beginning and map out a familiar, more optimistic plot line. They started a story being repeated elsewhere, reshaping the borough in its retelling. “Regeneration”, shouts the British Urban Regeneration Association, “is a comprehensive and integrated vision and action which leads to the resolution of urban problems and which seeks to bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental condition of an area”. This story of regeneration soars across Vonnegut’s blackboard, its narrative arc a neat line of progress and development. In Newham, it becomes the story of a plucky borough, once underperformer now leading-edger, sweeping us all up as supporting characters in a story bigger than ourselves.

I was stuck in this place that was falling — and I mean falling — down.

Regeneration is a story with compelling clarity. It fits neatly into templates for iconic plot lines. Christopher Booker would call it a “rebirth” story, or Joseph Campbell a “heroic monomyth” where trials are overcome to reap great reward. But telling a single story of a whole borough, constructing patterns out of the flowing soup of so many lives, means that a great many stories and the lives they describe are disregarded. To construct a single narrative from multiple stories requires a heavy-handed editor. For this active and considered process of exclusion, Paul Ricoeur offers the term “emplotment”, summarised by Jeff Leinaweaver as “boxing up narrative”, an act that exercises both “power and containment”.

So when I got here.

“We call Newham London’s supernova”, the executive director for regeneration and inward investment announces. “It is literally a platform waiting for things to happen. Traditionally it has always been one of London’s poorest areas and that situation hasn’t changed. To turn it around would be history in the making.”

It was just a house, but it was my house, you know?

The story of Newham needed a beginning and an ending, a moment when the chalk touches and leaves the blackboard. In his speech, the executive director for regeneration resets the beginning with three fresh starts, zero points on the narrative axis which relegate everything before to backdrop.

My husband Brian, his brother, he had this thing about that song “Nelly the Elephant”.

Newham is the site of a “supernova”, a plot device of implosive force to mark a beginning which burns away the clutter of history, experience, and place. After the dust has cleared, the setting for regeneration in Newham is revealed as a “platform”, an empty stage on which a new narrative can be played out. The existing local characters are also flattened, defined by a single economic condition — a poverty that “hasn’t changed”. With plot, setting, and characters in place, Newham is ready for a grand narrative, “history in the making”, the only story that will count.

And after I came home from the hospital after my op, he threw me about the room from one end of the room to the other, doing “Nelly the Elephant” in a jive.

The editorial power of emplotment overlooks or omits individual stories that no longer fit. But, as a narrative, regeneration would be no more and no less powerful than any other narrative about Newham, were it not for the power behind its telling. The story of regeneration, uttered so frequently and with such conviction, gains power and the patina of truth in every re-performance.

People must think now, “Ooh, look at them, living in places like that.”

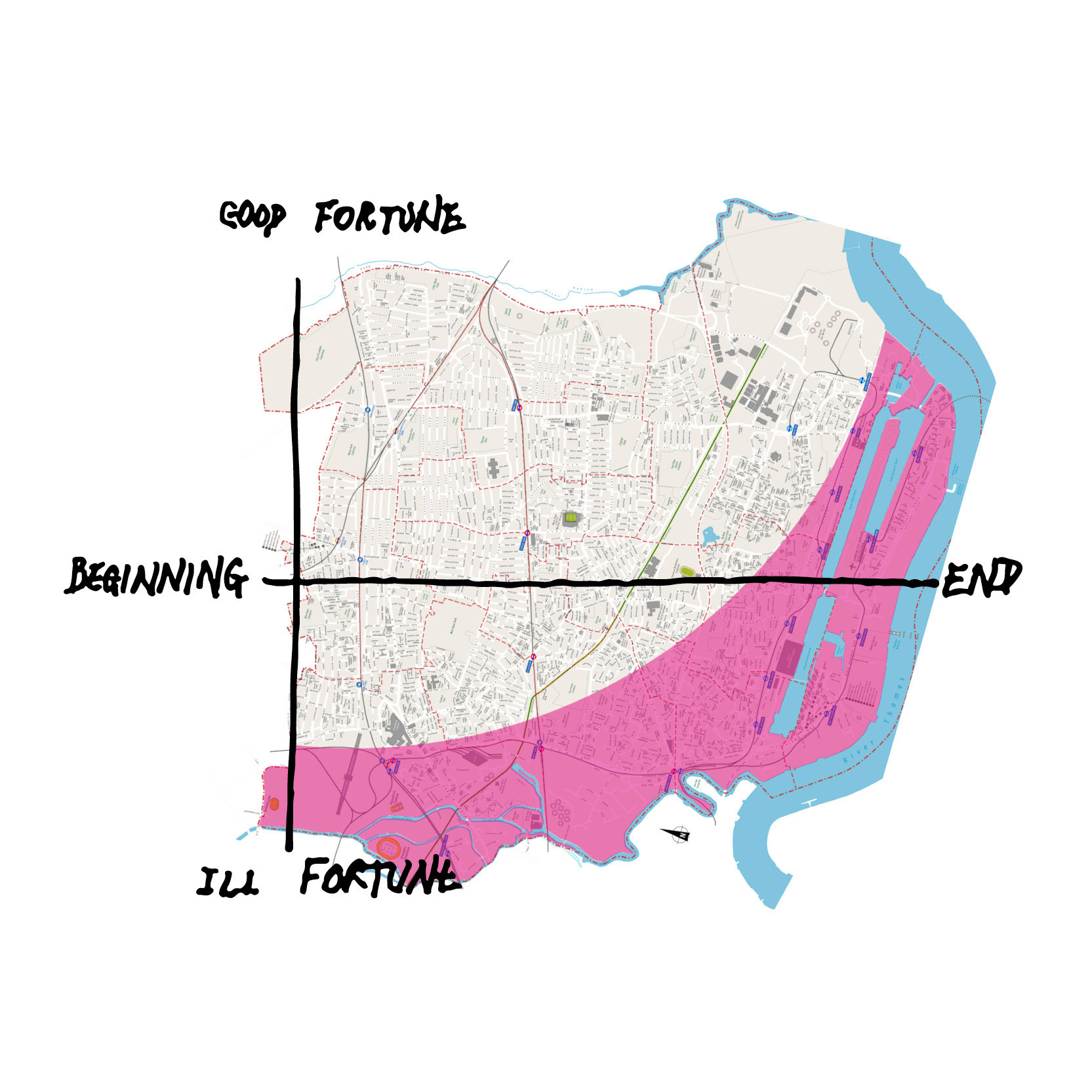

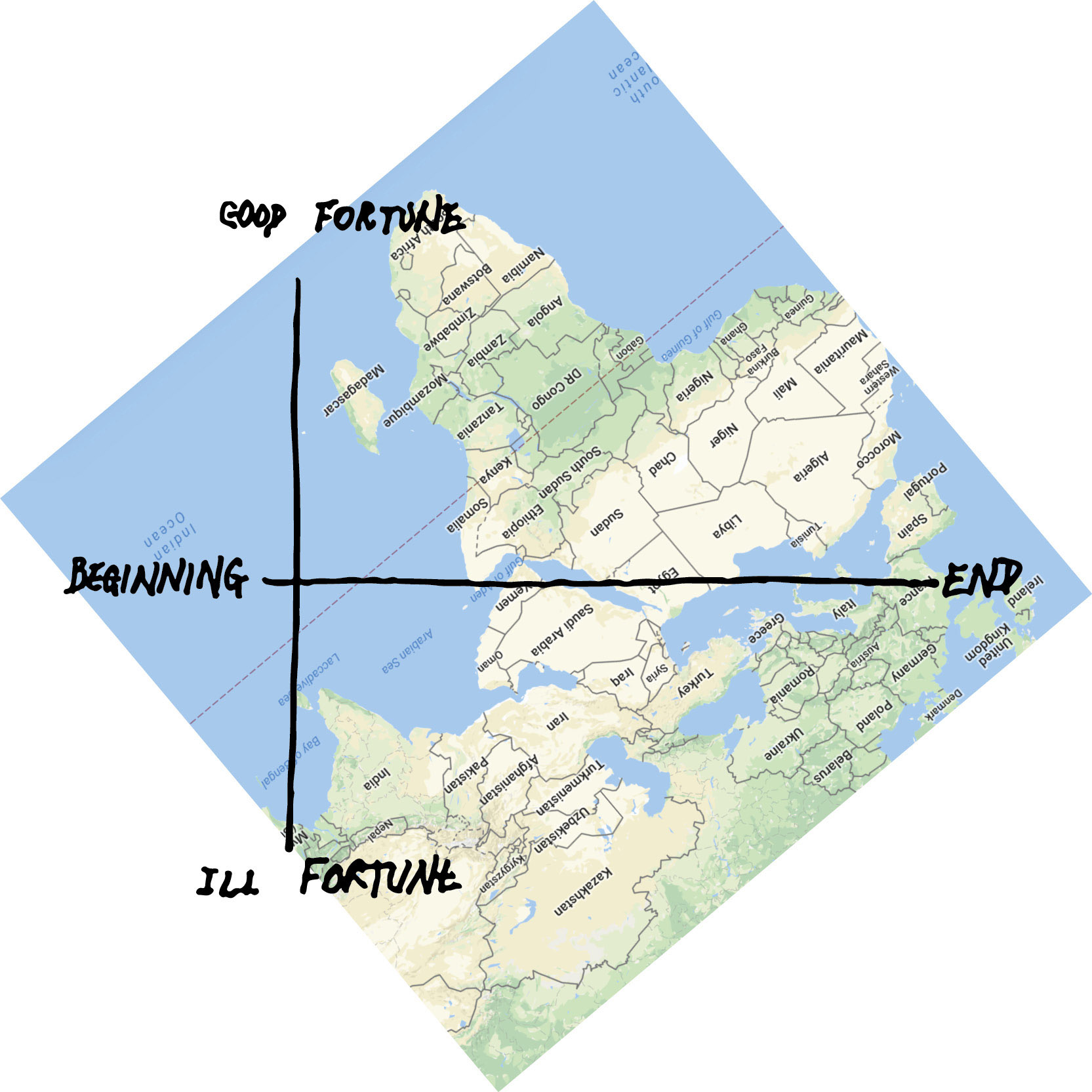

Imagine this: the blackboard is a map of the world. A single exponential curve is resized and redrawn across its continents. The men holding chalk beside it look proudly at the soaring line of their cut-and-paste arc. “The Arc of Opportunity”, states Transform Newham, “sweeps from the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park down the River Lea to the Thames, then eastwards throughout the Royal Docks to Gallions Reach and on into Barking”.

But they’ve not been inside them.

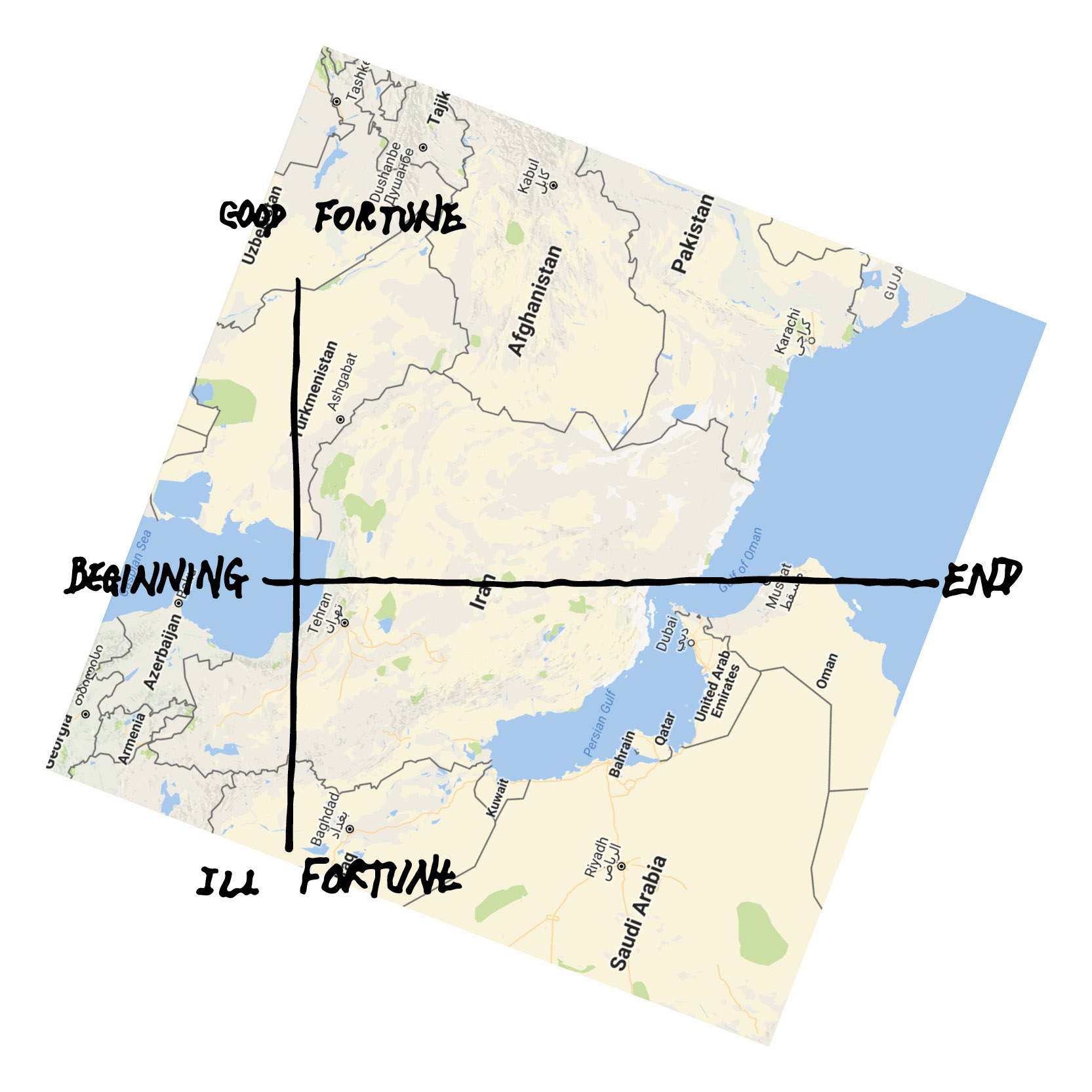

With the Arc of Opportunity the story of Newham found its shape. But arcs of opportunity did not begin in Stratford and will not end in Beckton. Two decades before the council first washed over Newham’s southeastern perimeter in pink, the cover illustrator of Time magazine warped the shores of the Indian Ocean through to the horn of Africa into an amber crescent. Within its pages Cold War diplomats and foreign correspondents wrangle over geopolitical strategy of this region rich in oil reserves rocked by Islamist revolution. As they question who will transform the “arc of crisis” into their “arc of opportunity”, the shape, identity, and destiny of this narrative is forged.

Don’t go by the appearance of what Mr Mayor has done, putting the boards up.

Arcs of opportunity, whenever they sprout and whatever region they sweep, have always been more politics than place. Just as narrative arcs shape the type of stories we tell, arcs of opportunity warp landscapes and lives, recasting spaces and peoples until paths of narrative promise align with geography. UK city councils seem particularly eager to impose trajectory on topography.

This is what I have to say to him:

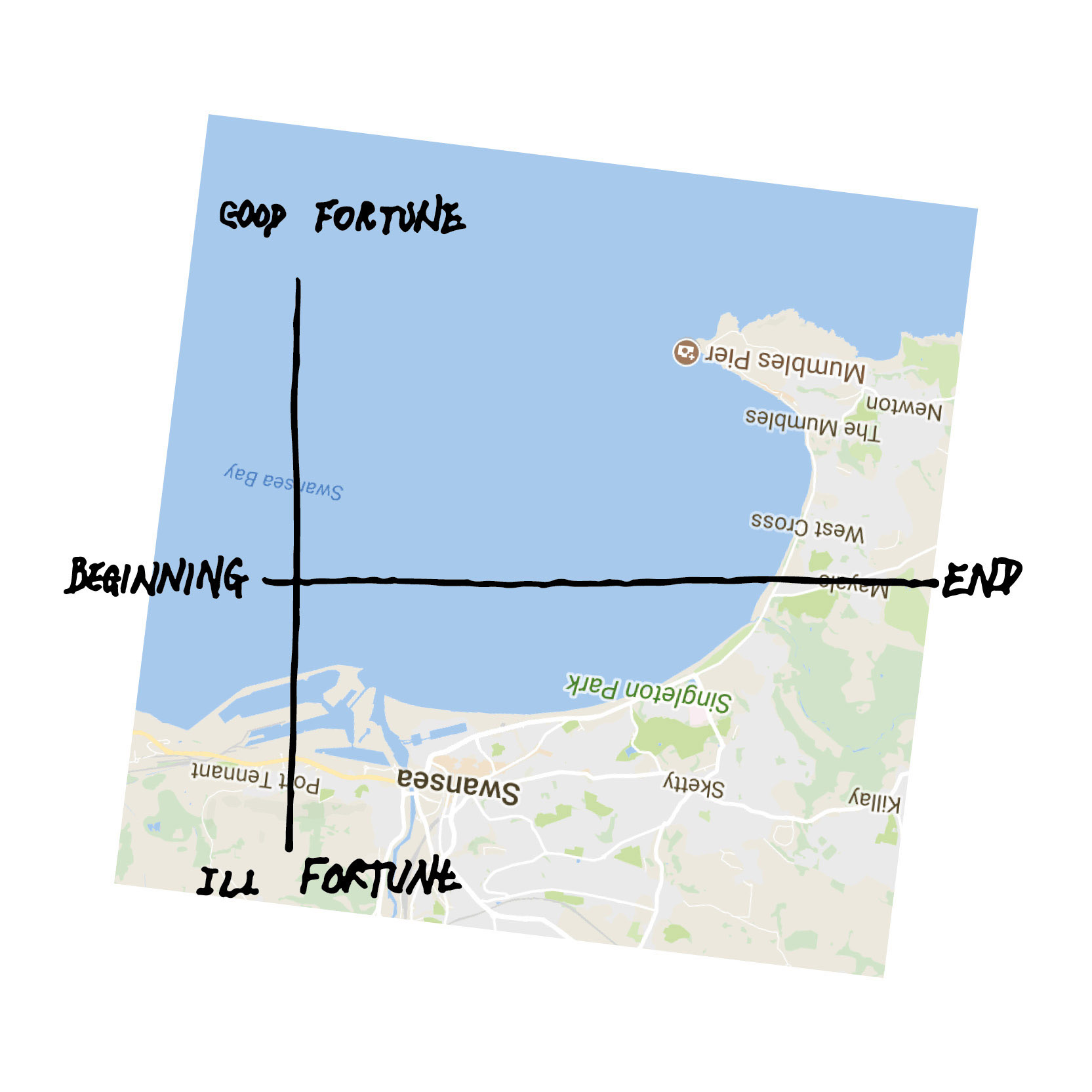

As policy papers and promotional videos smear the regeneration programme over Newham, eight further arcs of opportunity snake across the UK: stretching around the shore of Swansea Bay along the M4 Corridor ; extending from the University of Salford to the Oxford Road corridor ; spanning Dudley to West Birmingham ; creeping along the Leeds and Liverpool Canal west of Wigan ; lining the A451 in Kidderminster ; reaching across Halifax town centre ; swelling from the Waterfront to Victoria Street in Liverpool ; and striding along Fleming Way in Swindon.

“If you honestly think that I am going to give up my home to you at my time of life, forget it.”

And the arcs grow. From an isolated curl in the northwest of Adelaide ; to soaring sprawling spans throughout central Asia to Afghanistan ; across the South Pacific Rim ; circumnavigating Marrakesh to Bangladesh ; most recently returning to the UK to delineate the first round of new Garden Cities looping around the Green Belt from Southampton, Oxford, and Cambridge to Felixstowe.

“I will fight you.”

Applying a shape to something as complex as geography or politics is as simple as drawing the narrative arc of Hamlet on a chalkboard and just as absurd. Vonnegut’s students would laugh because it is too easy. But the power of the story is such that, on its own terms, stripped of all the complexity of life to distract or divert us, arcs of opportunity can feel true. Emplotment edits out other stories which might blur its beginning or fray its ending. But if we are able to resituate the grand narrative of regeneration, to see it for the story it is, we find it as vulnerable as any other. There is plenty of space on the blackboard to draw over it.

“You will have to drag me out.”

In this singular story, the idea of “Newham” is the main character, with Borough and Council indistinct. When residents reclaim an authorial role to cast themselves as protagonists the plot line of progress — the economic, physical, social, and environmental improvements promised in regeneration rhetoric — rarely feature. Those who study the impact of urban policy, such as Ben Campkin, Loretta Lees, Paul Watt, find that those cast in the story of regeneration are often cast out by its reality. Instead, support networks break, rents and other costs rise, and the people and activities that form and forge diverse communities are displaced.

“It belongs to me.”

Imagine this: On the blackboard a tangle of lines strike through and obscure Newham’s clean Arc of Opportunity, preceding its false beginning at the regeneration supernova and extending beyond the covenant of legacy. Beside it stand a cast of Newham residents who have given their voices and their stories to Music for Masterplanning. Amongst them, Mary Finch, whose words weave through this chapter. Her life on the Carpenters Estate becomes a story of resistance told by the Land of Three Towers, an all-female cast of housing activists, people who have experienced homelessness and young mothers. The power of stories grows with each retelling, the power to mutually renegotiate identity. These “fragmented, polyphonic, collectively produced stories” are what David Boje refers to as “antenarratives”. Their existence disrupts the “linear mono-voiced grand narrative”. Music for Masterplanning is a retelling of Newham. Each song is a performance of self, redressing the grand narrative that subjugates the stories of its residents. They are antenarratives that shatter the singular voice of regeneration into many pieces, to re-author life stories in all their complexity.